The Art of Collecting Christmas Music

Remember how record companies used to entice would-be customers to join their record clubs? You know, the mail-order offers of four or six or eight vinyl albums for only $.99 a pop as long as you purchased a minimum number of their selections-of-the-month or other albums of equal value? Columbia Record Club, which began the practice of marketing and distributing vinyl records in the late 1950s, led the way. RCA Record Club, a well as its Red Seal classical music label, and other record companies eventually followed suit.

Thirty years after hearing the sweet singing of carols by the Sisters of St. Joseph at my first Midnight Mass, I was in the process of assembling a small library of Christmas music. At the time I owned a medium-sized collection of pop and classical music, the latter for which I had acquired a taste during my teenage years, and my appreciation of Christmas music was definitely on the rise. To expand the library, I readily took advantage of Columbia and RCA marketing offers by enrolling in their record clubs. To maximize receiving benefits from each club, I would quickly fulfill my membership obligation by purchasing the minimum number of albums, and once I did, I would immediately cancel my membership. Since I was a member in good standing when I left, it wasn’t long before the same record clubs sent me new offers to join their clubs again. I almost always accepted, and the membership in-and-out cycle would repeat itself, thus enabling me to add significantly to my music library at a very reasonable cost.

But the record club that had the most impact on my assembling a substantial Christmas music library was The Musical Heritage Society of New Jersey. Like RCA’s Red Seal label, it too emphasized classical music as its reason d’être, and its annual Christmas catalog offerings, more generous and comprehensive in scope than the better known clubs, opened my eyes to the wonders of Renaissance, Baroque, and sacred music. What made these pre-CD era purchases possible were the amazing low prices, ranging from $2.50 and $5.45 per album or cassette.

My most memorable purchases, mostly from the Musical Heritage Society, included Michael Praetorius’ Christmas motets on period instruments, Italian Baroque Christmas concertos, colonial American hymns and carols, 15th-to-18th century English carols, especially those that were part of Benjamin Britton’s “A Ceremony of Carols,” and cantatas and oratorios by Back, Handel, and Mendelssohn. Adding to my delight were numerous albums of carols performed on a variety of instruments: organ, brass, harpsichord, panpipes, flute, carillon bells, harp, guitar, and music boxes. Other prized Christmas albums included performances by illustrious choirs and orchestras: the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, the Vienna Boys Choir, and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir with the Philadelphia Orchestra, just to name a few.

By 1988 as a result of my systematic low-cost approach in taking advantage of various record club promotions, I had become the proud owner of a substantial Christmas music library. Later that year as I was feasting on my second helping of Thanksgiving turkey, a light bulb went on: Why not share my acquired riches with family and friends for Christmas!

SPECIAL PERSON OF THE DAY: Thomas Alexander Lacey (December 20, 1853 – December 6, 1931)

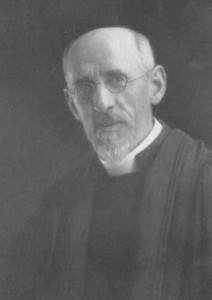

Rev. Thomas Alexander Lacey

Canon Lacey memorial at Worcester Cathedral

Buried in Garth cloister at Worcester Cathedral, England, are the remains of the Rev. Thomas Alexander Lacey, an Anglican priest, who died on December 6, 1931. His special contribution to the carol hymn repertoire was providing the most popular English translation O Come, O Come Emmanuel for “Veni, Emmanuel.” His translation of the Latin verses, which were based upon the great O Antiphons for the week prior to Christmas and are included in my first publication Best-Loved Christmas Carols (2000), first appeared in The English Hymnal (1906), a labor of love he had work on for many days and nights.

A great conversationalist and scholar noted of his expertise in Medieval Latin and Canon, Rev. Lacey lived the Christian ideal very much like John Mason Neale, another Anglican priest and the composer responsible for the adaptation of the Latin lyrics for Veni, Emmanuel. Both priests drew suspicion from their Anglican superiors because of their Catholic leanings, and in particular the Rev. Lacey was an apologist for the Anglo-Catholic position and devoted to the cause of ecclesiastical reunion. Both priests also worked among the less privileged or the afflicted. Lacey was a dedicated worker on behalf of girls in penitentiaries, and he once worked tirelessly during a typhus outbreak that occurred when he served at St. Benedict’s in Ardwick by persuading those infected and reluctant to leave their homes to allow him to carry them into ambulances.

Rev. Lacey eventually became assistant master of Denstone College and was made a Fellow of the College of St. Mary and St. John, Lichfield. That was followed by his appointment as vicar of St. Edmund, Northampton, then vicar of Madingley, Cambridge, and later as chaplain and then warden at the House of Mercy in Highgate, where there is ample testimony he had led a saintly life. In 1919 he was made Canon at Worcester in which capacity he served until his death.