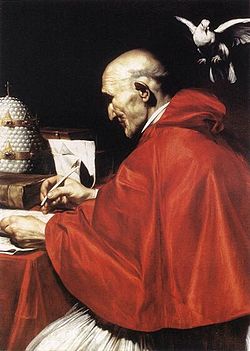

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: Pope Gregory the Great

Today is the Feast Day of Pope Gregory I, or Saint Gregory the Great (590-604 A.D.). He was born in a wealthy Patrician family, chose a solitary monastic life as a Benedictine monk after finding personal discontent as a public official, and then ultimately was elected as pope, the first monk to be elevated as pontiff. He is buried in St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome.

Gregory the Great was an important figure in the world of Western Music, one heavily influenced by church liturgy. His monastic life had brought him close to that music, providing him with the knowledge that it was highly unorganized. Although he bemoaned his elevation as pope, preferring instead the world of monastic piety and contemplation, Gregory took on the monumental task to codify and bring a sense of order to the literally thousands of church liturgical texts, most of them written in Latin.

Gregorian chant, i.e., Western chant or plainchant, was named after him because of his papal efforts to organize these large stores of church music. There is no definitive proof, however, that Gregorian chant stems from the late sixth century or at any time during Gregory’s fourteen-year rule as pope. The earliest manuscript found containing Gregorian chant dates from the ninth century and comes from the Frankish Empire.

What is not subject to question is Gregory’s desire to bring order and conformity to Church liturgy from the vast stores of sacred texts. His strong interest in music was supposedly demonstrated by his active collection of a rather large repertory of Roman chants, which may have numbered three thousand pieces at the time, and at his papal behest Roman chant would eventually spread throughout the continent and supersede all other chants in usage. Also, at his behest, monastic groups were formed to serve basilicas, the ancient churches of Rome accorded special ceremonial rites by the pope. These groups formulated chant based on verses from Psalms of the Old Testament, but there is no musical evidence to verify these chants as being Gregorian. One reason for this lack of evidence was that notation was still unknown.

One of the most important developments in the history of Western music, influenced by the ancient Greeks, who had practiced naming different music pitches with letters a thousand years earlier, notation evolved as a mnemonic device for singers who were already familiar with melody and words.

Notation quickly enhanced the growth of Gregorian chant, which by the eighth century was in competition with, or descendant of, other chants from the ancient Church, including Ambrosian, from the early Christian Church and named after St. Ambrose, the bishop of Milan; Mozarabic, from Spanish rites; Gallican, from ancient Gaul (France); Byzantine, from the Eastern Church; and Old Roman, from the earliest days of empire. There were other chants, of course, that existed then, as they have throughout all history, which served the impulses of primitive sects besides the more established religions of Eastern and Western societies.

By the ninth century the appearance of neumes provided for a measurement of pitch in music. It was also an age when Gregorian chant was maturing as a distinct entity largely as a result of the supersession and acceptance of Roman chant by Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire.

With the introduction of the musical staff and other notational devices during the 900-1050 period, it was possible to notate the relative pitch. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Gregorian chant was a thoroughly entrenched part of church liturgy throughout all Christian Europe. It was also during this time span when Gregorian chant enjoyed its greatest prestige.

There are two critical points about Gregorian chant worth noting: 1) it was sung unaccompanied by any musical instrument; and 2) it was an integral aspect of High Mass (or Solemn Mass), and other designated Church ceremonies or services, particularly the Divine Office.

For much of the late stages of first millennium and early High Medieval Era, the music heard in Christian churches during Advent and Christmas was likely to be Gregorian chant and sung in Latin. Vernacular carols would not become a part of Christmas celebrations until the 13th century.

In recent years Gregorian chant has become more familiar. Recordings of it are available and even popular, not so much as a counterweight to the incessant noise of the age but as soothing contemplative music whose early development was hugely influenced by Gregory the Great.

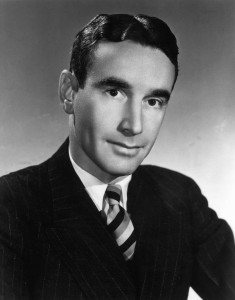

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: William Hayman Cummings

In August 1831 William Hayman Cummings was born in Sidbury, England. He was a musician, notable tenor, and organist who may be best known for his wedding of Felix Mendelssohn’s music to the Charles Wesley hymn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing. An accomplished musician, Cummings was educated at St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir School and the City of London School. He was also the founder of the Purcell Society, a reputable singing professor at the Royal Academy of Music and later a principal for the Guildhall School of Music.

Wesley, who co-founded the Methodist Church, originally titled his hymn as Hark! How All the Welkin Rings in the 1739 publication Hymns and Sacred Poems. The carol melody was adapted from a cantata that Mendelssohn wrote as part of his commission to compose music for the 1840 Leipzig Gutenberg Festival. That festival commemorated the 400th anniversary of the invention of the printing press by Johann Gutenberg. Six years later the teenage Cummings was a chorister for Mendelssohn’s first London performance of Elijah, the second of three oratorios composed by the German master.

Perhaps during that performance Cummings developed an admiration for Mendelssohn’s music and then in 1855 decided to link Mendelssohn’s music with Charles Wesley’s hymn. Thus on Christmas Day of that year, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing was first sung at Waltham Abbey with William Hayman Cummings at the organ.

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: Robert Lewis May

On this day in 1976, Robert Lewis May died. His fame rests as the author who in 1939 wrote the story of Rudolph for which his brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, wrote a tune in 1948 titled Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. By the following year it was released as a recording, one that would become one of the most successful Christmas songs of all time.

How Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer became a huge success began as a simple request by Robert May’s boss at Montgomery Ward, the mail-order giant. The advertising executive asked May, the department’s copywriter, to write a cherry Christmas story in booklet form with an animal theme for its customers. In previous years Montgomery Ward gave away coloring books to its customers, but decided in 1939 to create its own booklet to save money.

At the time May was beset with problems at home. His wife, Evelyn, was suffering from an advanced case of cancer. His station in life was considerably less than what he had been used to. Raised in an affluent Jewish family in New Rochelle, New York, and graduating from Dartmouth College in 1926 with Phi Beta Kappa honors, his road ahead seemed quite promising. Then the stock market crashed in 1929 and with it the loss of his family’s wealth. Sometime during the 1930s he moved to Chicago, taking on a low-paying job as a copywriter for Montgomery Ward.

May took to the task and began the story of Rudolph in earnest. Drawing upon his memory as a painfully shy child, he decided to use a singular reindeer as the main character for the story. He was also mindful that his daughter Barbara loved the reindeer at the Chicago Zoo. It was during that early stage of writing Rudolph in July 1939 when Evelyn died. In light of her death, May’s boss offered him release from the story assignment, but May refused. Spurred on by grief and by his daughter’s encouragement, May wrote and rewrote the story, constantly reading it to Barbara for her approval until both agreed in late August 1939 that the final version was ready for Montgomery Ward.

The story of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was first distributed to 2.4 million store customers during the 1939 Christmas season. They loved it! Due to World War II restrictions and the consequent shortage of paper, it wasn’t until 1946 when the company reissued the story to the tune of 3.6 million copies.

Although Montgomery Ward owned the copyright to the Rudolph story and despite the story’s tremendous appeal, Sewell Avery, the company president, as a gesture of eternal gratitude gave May the copyright to the story. Rudolph eventually was updated and published in 1947 as a colorfully illustrated book by a small New York publishing company. It became an instant best-seller.

May eventually married an employee of Montgomery Ward. Her name was Virginia, a devout Catholic, and together they had five children. May was also famous for growing the most amazing tomatoes, some of which grew to 12 feet tall. His fame,though, largely rests for penning a favorite holiday story that was borne out of grief and a sense of not belonging, ultimately becoming triumphant through the love of a child.

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: Guillaume Dufay

On this day in 1397 Guillaume Dufay was born. An important Franco-Flemish composer, he was instrumental in the transition from Medieval to Renaissance music. His reputation grew during his years in Italy when he earned the sobriquet as “the greatest ornament of our age.” He was also a Catholic priest who served the choir of the Papal Chapel in Rome from 1428 to 1443. It is understandable then why much of his musical output was devoted to church liturgy, including polyphonic works for Masses. motets, and hymns, some of which were dedicated to Advent and Christmas.

Dufay’s reputation asone of the most influential composers of the 15th century was well earned, evidence of which can be found in the works of succeeding composers who emulated some elements of his musical style. His embellishment of austere medieval plainchant by employing mellifluous harmonies made singing church music more pleasant to the ear, thus elevating church music of his day and further establishing the Mass as the main platform for elaborate polyphony.

The composer’s music appeal also extended into the secular realm, for there he also made his mark felt, and his melodic style would ultimately became characteristic of the early Renaissance. There is little doubt about Dufay’s unique contributions to the evolution of Western music, and today he still holds a special place in the pantheon of great composers.