In The Bleak Mid-Winter

Published posthumously in 1904, ten years after the death of Christina Rossetti (1830-1894), the poem In the Bleak Mid-Winter would two years later become a plaintive and haunting Christmas carol. Written by Rossetti sometime before 1872, it was not intended as a carol or hymn, but as a Christmas poem at the behest of Scribner’s Monthly, an American literary magazine.

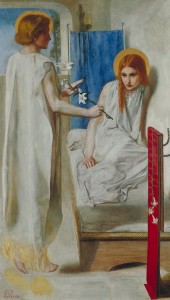

Rossetti was one of the few hymn writers of her day who garnered a reputation as a poet. She was highly supported by an educated and artistic family. Her father came to England as an Italian patriot and refugee who would become a professor at King’s College in London. Her brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), was also a poet although he earned greater distinction as a Pre-Raphaelite artist. Possessed of exceptional beauty, Christina often posed as a model for her brother (and other contemporary artists), such as in his unique interpretation of the biblical Annunciation scene with Ecce Ancilla Domini. Sadly she was also known to have suffered her own pain and disappointment, some of which registered as somber verse in the manner of Emily Dickinson, the reclusive American poet.

Gustav Holst (1874-1934), a long-time friend of the celebrated Ralph Vaughan Williams, had a keen interest in Rossetti’s works. Best-known for his classical pieces, notably his orchestral masterpiece The Planets, Holst elevates In the Bleak Mid-Winter with a hymn-like musical setting that was published in the 1906 English Hymnal. Another popular setting for Rossetti’s contemplative poem was produced in 1909 by the English composer, Harold Edwin Darke (1888-1976), while he was a student at the Royal College of Music. His version has been favored by cathedral choirs over the years and it is often featured as part of the Nine Lessons and Carols, the annual Christmas radio broadcast by the King’s College Choir of Cambridge.

Despite England’s long tradition of producing and publishing exceptional carols, In the Bleak Midwinter was voted the greatest Christmas carol of all time in a 2008 poll of English choral experts and choirmasters. This is not at all surprising if your tastes prefer superb Christmas choral singing. Listen closely to the plaintive tune and imagine the gripping scene first depicted in Rossetti’s poem: snow falling on a bitterly cold night, the bleakness of winter, the meager environment attended by a loving and attentive mother in the presence of heavenly angels, stable animals, and lastly a lonely poet humbly offering her heart, her most precious of gifts, to the new-born child Jesus.

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: William Hayman Cummings

In August 1831 William Hayman Cummings was born in Sidbury, England. He was a musician, notable tenor, and organist who may be best known for his wedding of Felix Mendelssohn’s music to the Charles Wesley hymn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing. An accomplished musician, Cummings was educated at St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir School and the City of London School. He was also the founder of the Purcell Society, a reputable singing professor at the Royal Academy of Music and later a principal for the Guildhall School of Music.

Wesley, who co-founded the Methodist Church, originally titled his hymn as Hark! How All the Welkin Rings in the 1739 publication Hymns and Sacred Poems. The carol melody was adapted from a cantata that Mendelssohn wrote as part of his commission to compose music for the 1840 Leipzig Gutenberg Festival. That festival commemorated the 400th anniversary of the invention of the printing press by Johann Gutenberg. Six years later the teenage Cummings was a chorister for Mendelssohn’s first London performance of Elijah, the second of three oratorios composed by the German master.

Perhaps during that performance Cummings developed an admiration for Mendelssohn’s music and then in 1855 decided to link Mendelssohn’s music with Charles Wesley’s hymn. Thus on Christmas Day of that year, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing was first sung at Waltham Abbey with William Hayman Cummings at the organ.

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: Rev. John Mason Neale

On this day in 1866, the Rev. John Mason Neale died. A humble and scholarly Anglican priest, his reputation largely rests with his research and translations of ancient Greek and Latin religious texts, tasks that must have come easily to him since he was proficient in twenty-one different languages. The contributions of Neale to the revitalization of ancient and medieval church hymns and his deft translations of them cannot be underestimated. The brilliant scholar was known to have lamented the Reformation’s neglect of the rich history of hymnody, despite the movement’s praiseworthy restoration of worship and song to the language of the common people.

The Rev. Neale was also a well-respected composer of Christmas carols and hymns, some of which were delivered as a result of translating centuries-old hymns and songs, including those of a secular strain.

Three of those carols have grown quite popular since the publication of his 1853 collection Neale’s Carols for Christmastide. The most sacred was the carol hymn Veni, Emmanuel (O Come, O Come Emmanuel) based upon the Latin great O Antiphons of Advent whose seven verses are believed to have been composed by monastery monks who sang one verse per day at Vespers, the late afternoon or early evening canonical hour of prayer, for seven straight days prior to Christmas Eve.

Good Christian Men, Rejoice, the second carol, was Neale’s loose English translation of one of Germany’s best-loved carols, In Dulci Jubilo. Neale found the melody of this medieval Latin-German carol in Piae Cantiones, the famous 1582 Swedish book of carols that also produced the tune for Good King Wenceslas, the third familiar carol. For the latter, Neale was looking for a good role model for children. He found it in King Wenceslas of Bohemia who was known to be a just and merciful king and having considerable compassion for the poor and sick.

It could be said that King Wenceslas was also a role model for Neale himself since he, too, led an exemplary life by dedicating his life to the less fortunate. The hymn composer had a penchant for caring for the lowliest on society’s scale, and his Christian deeds set him apart from other clerics holding more lofty positions in the Anglican Church.

Such was Neale’s station in life that his own bishop, imagining Neale of Roman Catholic leanings, prohibited him from performing any ministerial duties and relegated him to a seemingly less desirable post. Thus, in 1846 Neale was made warden of Sackville College, a position he held for the rest of his life. Sackville College, however, was actually an almshouse, a charitable residence for the poor and aged. Twelve years later the humbly intrepid, and often frail and sickly, Neale founded the Sisterhood of St. Margaret, a group dedicated to the poor, needy, and suffering. For this charitable effort he was accused of a return to nuns, again earning him the enmity of Church authorities that thought he was converting to the Roman Catholic faith. Neale’s ministry later established an orphanage, a school for girls, and a home for unwed mothers, the latter forced to close due to church and local opposition. In a nutshell, Neale’s dedication to serving the poor and indigent was on a level with that of his work with sacred texts and hymns. Each pursuit was performed tirelessly, with dignity, and for the higher good.

Emmanuel, meaning “God with us,” is a splendid title for a carol hymn. It must have held special significance to Rev. Neale as he worked among the poor. The title reaffirms the religious concept of Christ’s birth as God Incarnate dwelling among men and announcing to them his mission here on earth. In the world of the ancient Hebrew, the choice of name was made judiciously, as the name Emmanuel must have been for Neale. For the scholarly Anglican priest, the name radiated in bold light and demonstrated, coincidentally, his own essential character and purpose as a man.

Today the Rev. Neale lays in peace at St. Swithun churchyard in East Grinstead, England, close to Sackville College where he abundantly served so well those who had so little.