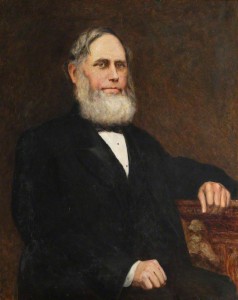

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: John Troutback

On this day in 1832, John Troutback was born in Blencowe, Cumberland, England. He was a noted English translator of famous musical texts and an Anglican priest who served as chaplain to Queen Victoria during his tenure as Minor Canon at Westminster Abbey (1869-1899). The Rev. Troutback had previously held the position of Precentor at Manchester Cathedral from 1865-1869.

For purposes of distinction in the Anglican Church, a Minor Canon is usually a junior clergy staff member of a cathedral or collegiate church who participates in daily services. A Precentor, too, is a clergy member, generally part of a large church, whose charge is to prepare and organize liturgy and worship services.

The Rev. Troutback arranged many of the royal services at Westminster Abbey, most notably the 1887 Golden Jubilee service for Queen Victoria. In addition to devoting much of his life’s energy to church music, including editing Westminster Abbey Hymn Book (1883), several chant books, and The Manchester Psalter a few years prior to his assignment to Westminster Abbey. A possessor of a very fine voice, he was also the author of Church Choir Training.

Troutback’s greatest claim to fame, however, was his English translations of German, French, and Italian operas, songs, and oratorios for the British music publisher Novello. The Who’s Who List of his translations included Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, St. John Passion, Magnificat, and Christmas Oratorio.

The Christmas Oratorio (German Weihnachts-Oratorium) by Bach was one of three oratorios written near the end of his career and his last major contribution to the Lutheran Church. It was intended to conform to the church calendar for the 1734 Christmas season and to be performed on six successive Sundays during Advent and the Christmas season at two churches – St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in Leipzig. The oratorio incorporated six cantatas from earlier Bach compositions, some of them secular in tone, which caused some Lutheran Church elders to have problems with the great composer’s discarding of some hymn texts in favor of poetical passages and the interjection of a number of chorales, choruses, and arias of a non-Scriptural nature into the sacred work. The oratorio’s recitative and chorale settings, however, were original Bach compositions.

Bach received inspiration for his work from both the St. Luke and St. Matthew versions of the Nativity, especially since together they gave a more complete narrative of Christ’s birth. He believed the St. Luke 2:1-21 gospel had greater poetic qualities than the gospel of St. Matthew 2:1-12. However, St. Matthew’s story was particularly attractive to Bach since it recounted the tale of the Three Wise Men, leading Bach to attach greater significance to the Magi in the concluding passages of the oratorio.

The finished oratorio was broken into six parts, each to be performed on one of the major feast days of the Christmas period as follows:

Part I: The Birth of Jesus (Christmas Day)

Part II: The Annunciation to the Shepherds (December 26)

Part III: The Adoration of the Shepherd (December 27)

Part IV: The Circumcision and Naming of Jesus (New Year’s Day)

Part V: The Journey of the Magi (First Sunday after New Year)

Part V: The Adoration of the Magi (Epiphany – January 6).

Despite its original three hour length, the Rev. Troutback must have been elated to take on the task of translating Bach’s marvelous Christmas opus. In 1874 Novello published it along with Rev. Troutback’s English translation of Bach’s Magnificat.

For his distinguished service to his church, the Rev. Troutback in now buried with his wife in the East Cloister of the Westminster Abbey.

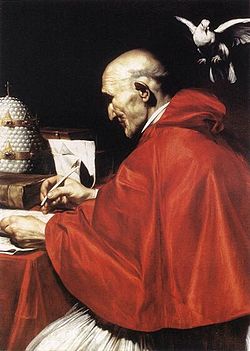

Christmas Classics PERSON OF THE DAY: Pope Gregory the Great

Today is the Feast Day of Pope Gregory I, or Saint Gregory the Great (590-604 A.D.). He was born in a wealthy Patrician family, chose a solitary monastic life as a Benedictine monk after finding personal discontent as a public official, and then ultimately was elected as pope, the first monk to be elevated as pontiff. He is buried in St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome.

Gregory the Great was an important figure in the world of Western Music, one heavily influenced by church liturgy. His monastic life had brought him close to that music, providing him with the knowledge that it was highly unorganized. Although he bemoaned his elevation as pope, preferring instead the world of monastic piety and contemplation, Gregory took on the monumental task to codify and bring a sense of order to the literally thousands of church liturgical texts, most of them written in Latin.

Gregorian chant, i.e., Western chant or plainchant, was named after him because of his papal efforts to organize these large stores of church music. There is no definitive proof, however, that Gregorian chant stems from the late sixth century or at any time during Gregory’s fourteen-year rule as pope. The earliest manuscript found containing Gregorian chant dates from the ninth century and comes from the Frankish Empire.

What is not subject to question is Gregory’s desire to bring order and conformity to Church liturgy from the vast stores of sacred texts. His strong interest in music was supposedly demonstrated by his active collection of a rather large repertory of Roman chants, which may have numbered three thousand pieces at the time, and at his papal behest Roman chant would eventually spread throughout the continent and supersede all other chants in usage. Also, at his behest, monastic groups were formed to serve basilicas, the ancient churches of Rome accorded special ceremonial rites by the pope. These groups formulated chant based on verses from Psalms of the Old Testament, but there is no musical evidence to verify these chants as being Gregorian. One reason for this lack of evidence was that notation was still unknown.

One of the most important developments in the history of Western music, influenced by the ancient Greeks, who had practiced naming different music pitches with letters a thousand years earlier, notation evolved as a mnemonic device for singers who were already familiar with melody and words.

Notation quickly enhanced the growth of Gregorian chant, which by the eighth century was in competition with, or descendant of, other chants from the ancient Church, including Ambrosian, from the early Christian Church and named after St. Ambrose, the bishop of Milan; Mozarabic, from Spanish rites; Gallican, from ancient Gaul (France); Byzantine, from the Eastern Church; and Old Roman, from the earliest days of empire. There were other chants, of course, that existed then, as they have throughout all history, which served the impulses of primitive sects besides the more established religions of Eastern and Western societies.

By the ninth century the appearance of neumes provided for a measurement of pitch in music. It was also an age when Gregorian chant was maturing as a distinct entity largely as a result of the supersession and acceptance of Roman chant by Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire.

With the introduction of the musical staff and other notational devices during the 900-1050 period, it was possible to notate the relative pitch. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Gregorian chant was a thoroughly entrenched part of church liturgy throughout all Christian Europe. It was also during this time span when Gregorian chant enjoyed its greatest prestige.

There are two critical points about Gregorian chant worth noting: 1) it was sung unaccompanied by any musical instrument; and 2) it was an integral aspect of High Mass (or Solemn Mass), and other designated Church ceremonies or services, particularly the Divine Office.

For much of the late stages of first millennium and early High Medieval Era, the music heard in Christian churches during Advent and Christmas was likely to be Gregorian chant and sung in Latin. Vernacular carols would not become a part of Christmas celebrations until the 13th century.

In recent years Gregorian chant has become more familiar. Recordings of it are available and even popular, not so much as a counterweight to the incessant noise of the age but as soothing contemplative music whose early development was hugely influenced by Gregory the Great.