Christmas Carols Documentary

Program Summary

Subject:

Fascinating Christmas Carol Stories.

Program Length:

60 minutes (possibly more)

Source Material:

275 color plates and illustrations

130 music tracks from the Collections

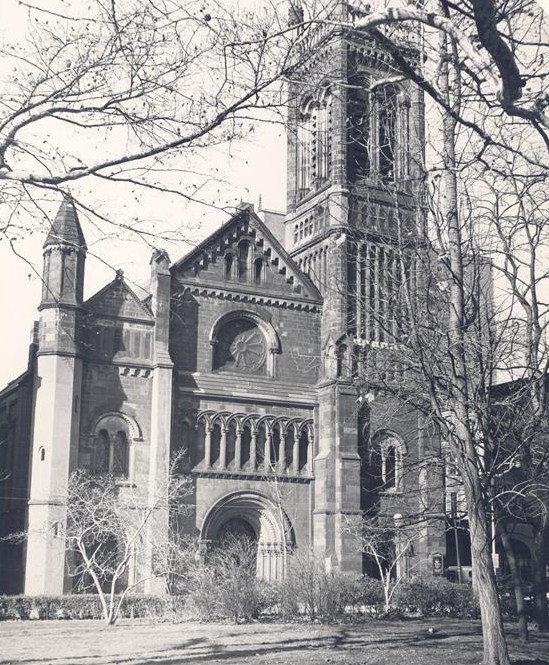

500 photos and portraits of Christmas music composers, lyricists, carol publishers, music manuscripts, churches, churchyards, misc.

24 YouTube Videos

Introduction:

Christmas music may be rightly considered the best-selling music in the world. Do you know that Americans and people from the Western World purchase millions of Christmas music albums yearly? Those are pretty impressive numbers! How many of them know anything about the origins of Christmas carols? Or about the contributions of European and American composers and songwriters to the international Christmas music repertoire? Surprisingly, the answer is very few.

How many people know “O Holy Night” (Cantique de Noel), an exquisite French carol, was initially detested by Church authorities. Or that the great German composer Felix Mendelssohn was commissioned to write the music for a festival celebrating the 400th anniversary of Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, then had it coupled, much to his chagrin, to the words of Charles Wesley’s hymn, “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing,” by an enterprising organist from England. Or that monastery monks sang one stanza of the haunting seven-verse “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel” hymn at Vespers, the early evening canonical hour, for seven days before Christmas Eve.

Regarding American contribution to the genre, there is much to explore. What did Christmas music sound like during the Revolutionary War period? What American Christmas carol’s Peace on earth, goodwill to men theme never mentioned the birth of Christ? What about the contributions of enslaved Black people? Their spirituals, notably “Mary Had a Baby” and “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” further enriched the Christmas folk music catalog.

How many people know “I Wonder As I Wander, an Appalachian carol gem, was discovered by John Jacob Niles, one of America’s great folklorists, at a revival meeting in a small North Carolina town.

The backdrop of such holiday classics as “The Christmas Song” and “White Christmas” provides fascinating insight into their origins. Can anyone top the mellifluous Nat “King” Cole as he sings, “Chestnuts roasting over on an open fire?” Ask members of The Greatest Generation who better than Bing Crosby can croon Irving Berlin’s all-time classic. And is there any more nostalgic song than “I’ll Be Home For Christmas?”

Some carols were explicitly written for children’s religious education. “Once in Royal David’s City,” penned by the wife of the Primate of Northern Ireland, is an excellent example. Or that an Anglican priest and author of the English lyrics for “Good King Wenceslas” wanted a good role model for children.

Christmas music existed many centuries before the popularity of carols. It was mainly associated with Church liturgy through chant, Latin prayers, and hymns. Its development from the early centuries of Christianity to the twentieth century is a fascinating adventure into the world of Western music.

Along the way, we learn that it was not until the fourth century that December 25th was officially declared a Church feast day to celebrate The Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Or that “Christmas” comes from the Old English Cristes maesse, meaning the Mass of Christ. We also learn about the ancestral roots of gift-giving and Christmas tree trimming as part of the journey.

Wouldn’t such a documentary be a worthy gift for the television audience during the Christmas holidays? Wouldn’t the favorite sounds of Christmas and the glorious art and illustrations be frosting on the cake?

Sample Stories

Carol of the Bells

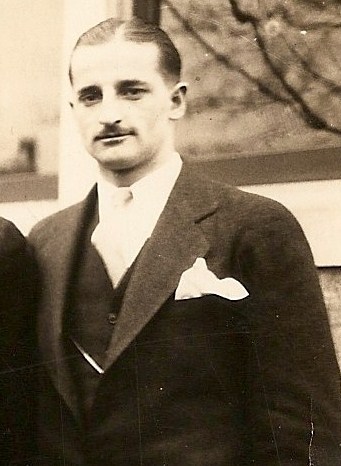

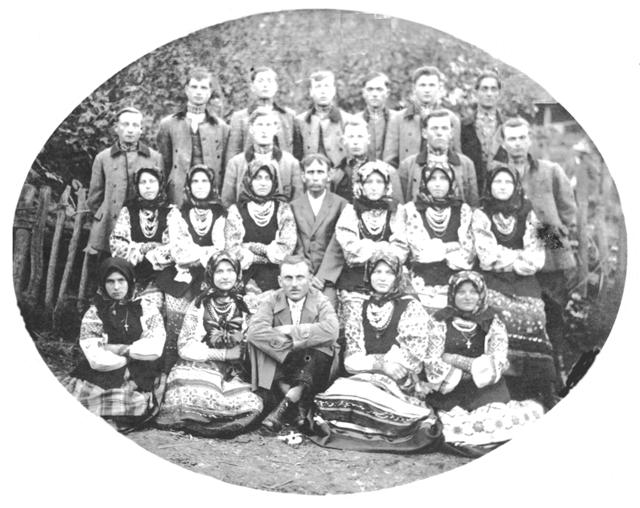

When Ukraine gained independence after World War I, the newly formed government sent the Ukrainian National Choir worldwide as its goodwill ambassador. The choir toured for five years singing a repertoire of Ukrainian songs, including “Shchedryk,” a fascinating New Year’s composition by Mykola Dmytrovych Leontovych. The song’s tintinnabulation sound enthralled European and American audiences, inspiring an American schoolteacher named Peter Wilhousky. He wrote the English carol lyrics and wedded them to Leontovych’s music under “Carol of the Bells.”

Wilhousky was propelled to national prominence when invited to prepare a student chorus to sing his “Carol of the Bells” for the National Association of Teachers of Music convention and its opening ceremony at Madison Square Garden in New York. For a year beforehand, he spent afternoons in each of the five New York boroughs auditioning, selecting, and training voices for this event. On March 30, 1936, before 16,000 people, his chorus of 1500 students filled Madison Square Garden with a magnificent sound that astonished the music teachers present.

O Come, O Come, Emmanuel (Veni, Emmanuel)

Reputedly, the hymn tune for “Veni, Emmanuel” comes from monastery monks. They sang one of the seven verses each day at Vespers, the late afternoon or early evening canonical hour of prayer, for seven straight days before Christmas Eve. The original words came from Latin antiphons known as the famous Seven Greater Antiphons, or Great “O” Antiphons of Advent because each verse follows the same cry of longing with the interjection “O” for the Messiah as he was addressed in various Old Testament texts.

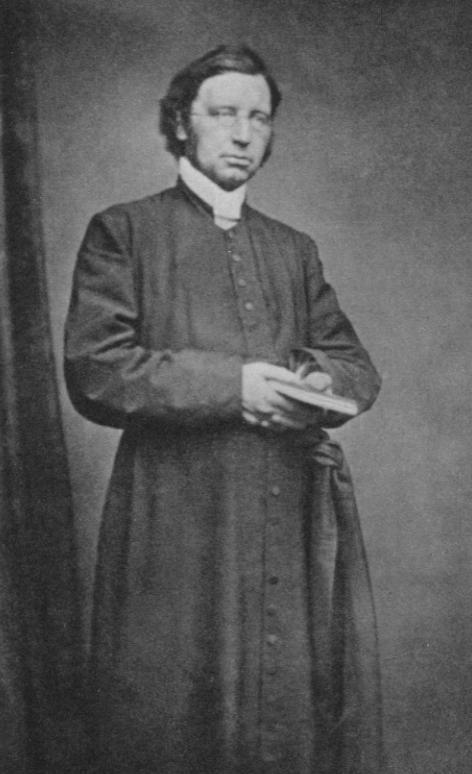

The English version, “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel,” was the creation of Rev. John Mason Neale, a humble, scholarly, and somewhat eccentric Anglican priest who was never adequately appreciated by his own Church. The task probably came easy for Neale, a hymn composer and noted translator of ancient Greek and Latin religious texts, since he was proficient in twenty-one languages.

The Anglican priest also wrote the English lyrics for two other carols: “Good Christian Men Rejoice” and “Good King Wenceslas,” the latter serving as a good role model for children. The brilliant scholar was known to have lamented the Reformation’s neglect of the rich history of hymnody. As a result of his ceaseless efforts working with ancient hymn texts, Neale resurrected the much beloved “Veni, Emmanuel” from obscurity.

Rev. Neale led an exemplary life. He had a penchant for caring for the lowliest on society’s scale, and his Christian deeds set him apart from other clerics holding more lofty positions in the Anglican Church. Such was Neale’s station in life that his bishop, imagining Neale of Roman Catholic leanings, prohibited him from performing any ministerial duties and relegated him to a seemingly less desirable post. Thus, in 1846, Neale was made warden of Sackville College, a position he held for the rest of his life.

Sackville College, however, was not a college at all! It was an almshouse, a charitable residence for the poor and aged. Twelve years later, the Rev. Neale founded the Sisterhood of St. Margaret, a group dedicated to the poor, needy, and suffering. For this charitable effort, he was accused of a return to nuns, earning him again the enmity of Church authorities who thought he was switching to the Roman Catholic faith. Neale’s ministry also established an orphanage, a school for girls, and a home for unwed mothers. The latter was forced to close due to church and local opposition. In a nutshell, Neale’s dedication to serving the poor and indigent was on a level with that of his work with sacred texts and hymns. Each pursuit was performed tirelessly, with dignity, and for the higher good.

Emmanuel, meaning “God with Us,” is a splendid title for the carol hymn, and it must have held special significance to Rev. Neale as he worked among the poor. The title reaffirms the religious concept of Christ’s birth that God incarnate had come to dwell among men. In ancient Hebrew, the choice of name was judicious, as Emmanuel must have been for the scholarly Neale.

O Holy Night (Cantique de Noël)

Written in 1847 and first performed at a Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve the same year, this carol eventually became much disliked by French church authorities even though they initially loved it.

The clergy’s repudiation of the carol, composed by Placide Cappeau, a wine merchant and mayor of Roquemaure, France, may have come about because of Cappeau’s socialist leanings and his later renunciation of both Christianity and his 1847 lyrics. The Church’s antipathy also may have stemmed from the realization that the music composer, Adolphe Adam, was a Jew and a friend of Cappeau. Adam was best known for his ballet, the well-acclaimed Giselle.

French churchgoers, however, had an entirely different reaction to this exotic new carol: it was pretty popular with them. Perhaps after witnessing the congregation’s response to the carol, French clerics restored it to its former exalted position.

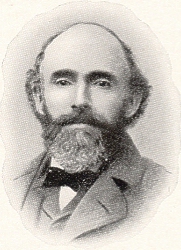

Across the Atlantic Ocean, “Cantique de Noël” caught the eye of John Sullivan Dwight, a Unitarian minister in Northhampton, Massachusetts, who eventually had to leave the ministry, becoming a recluse, because he became deathly ill when he had to address his congregation.

Dwight was also a music scholar of note who co-founded the Harvard Music Society and, as such, fell in love with the French carol and translated it into the English “O Holy Night.”

On another note, in 1906, at 9 p.m. on Christmas Eve, Reginald Fessenden, a Canadian-born inventor and pioneer in developing radio technology, sent music over the airwaves. Wireless operators of several ships at sea first heard Fessenden reciting the Nativity gospel before playing “O Holy Night” on the violin, thus making it the first carol heard on the radio.

O Little Town of Bethlehem

“O Little Town of Bethlehem” was a poem written three years after the Rev. Phillips Brooks of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Philadelphia traveled to the Holy Land. There, he was impressed by Christmas Eve services at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. As he sat on a hill looking back at the village, shepherds still watched their flocks at night, and he felt at peace with himself. He later told friends, “That experience was so overpowering that forever there will be a singing in my soul.” That experience came at a critical moment for one of the most influential preachers of his day. Because he was so personally affected and drained by the horrors of the Civil War, the Rev. Brooks could not preach when asked at the 1865 funeral of President Abraham Lincoln.

The children of his Sunday school were delighted with the tender poem, thus prompting the young rector to persuade Lewis Redner, a wealthy real estate executive, and the church organist, to set it to music well before Christmas day. Redner put off finishing the task because he could not overcome a musical obstacle. However, the night before the music was due for delivery, he had a dream inspiring him to immediately arise and complete the tune. A few days later, on December 27, 1868, his Sunday School children happily sang “O Little Town of Bethlehem“ for the first time.

Silent Night (Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht)

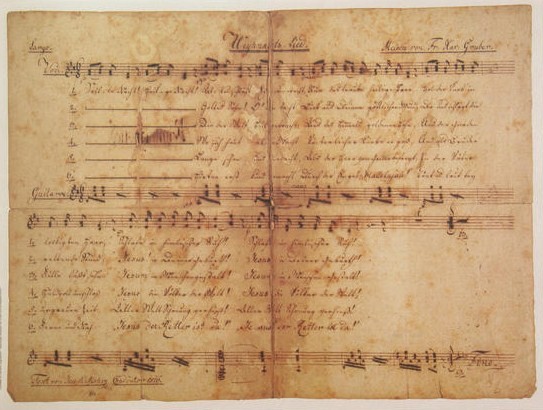

Perhaps the best-known Christmas carol of all time, “Silent Night,” has a fascinating history. According to legend, on Christmas Eve in 1818, Franz Gruber, the church choir director, had to quickly improvise the music for the poetic lyrics of Joseph Mohr, a Catholic priest, because the organ of his small village church had broken down. But Father Mohr had written the six-stanza poem “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht” two years earlier before asking his friend Gruber to set it to music before the Christmas Eve Mass. Gruber composed the now-familiar melody in an arrangement for two voices and a guitar. Since the guitar was not an approved instrument for Mass, Gruber and Rev. Mohr waited until the conclusion of Christmas Eve service before debuting the new carol. Mohr sang tenor and strummed the guitar while Gruber sang bass, and the congregation joined the chorus.

Six or seven years after its initial church performance, an organ repairman hired to reconstruct the organ at St. Nicholas Church found a copy of the carol and received permission to take it home with him. Soon after, traveling singing groups began to sing “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht” in different parts of Austria and other countries.

When King Frederick Wilhelm IV of Prussia first heard it, he directed his court musicians to find out who the composer was, a directive that may have spared “Silent Night” from obscurity. He also decreed it should be sung for him every Christmas Eve, leading to a tradition for it to be performed yearly in a special 5 p.m. service at the St. Nicholas Church.

Considered a national treasure in Austria, “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht” became popular throughout Europe. On Christmas Eve 1839, it was first performed in America by a touring Austrian choir before the tomb of Alexander Hamilton in New York City’s Trinity churchyard. Twenty years later, Rev. John Freeman Young, who would become an assistant rector at Trinity Church, produced the truncated three-stanza translation of “Silent Night,” today’s most sung English version.

The carol became exceptionally popular In the United States after World War I when returning veterans remembered hearing it sung by German soldiers during a Christmas truce. In 1918, the people of Wagrain, Austria, planned to erect a statue of their beloved Rev. Mohr to celebrate the carol’s 100th anniversary, but there were no known portraits of him. Mohr’s skull was subsequently exhumed and sent to a forensic artist in Vienna, who produced a likeness. The memorial statue and the skull eventually went to Oberndorf, with the latter placed beneath the St. Nicholas Church altar.

As a result of the creative labors of Rev. Mohn and Gruber, the Christmas music repertoire benefitted with what would become one of the “world’s most beloved carols.”

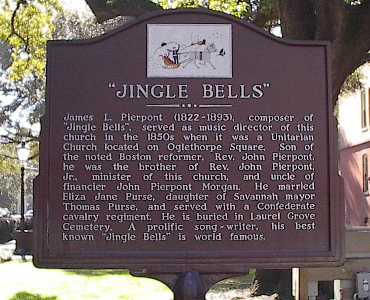

Jingle Bells

One of the most popular Christmas carols, “Jingle Bells,” was reputedly written by James Lord Pierpont for an 1840 Thanksgiving program at a Medford, Massachusetts, Unitarian Church, where his father, a fervent abolitionist, served as minister. In later years, James Pierpont sought adventure on whaling ships and prospecting during the California Gold Rush until his 1849 return to Medford.

Some authorities believed “Jingle Bells,” originally titled “One Horse Open Sleigh,” was composed in 1857, but that was the year the carol was copyrighted in Savannah, Georgia, where Pierpont was music director and organist for a Unitarian church ministered by his brother John. Today, that house of prayer is also known as the “Jingle Bells Church.”

Over the years, a difference of opinion about the birthplace of “Jingle Bells” has caused considerable dispute between Medford and Savannah city officials. Medford seems more likely to hold the rightful claim since sleigh races were commonplace in snowy New England during the 1800s.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, the two Pierpont brothers found themselves on opposite sides of the battle lines. John returned to Boston and served as a chaplain for the Union Army, but for his part, James served with the First Georgia Cavalry and contributed several songs to the Confederate effort. He ceased writing songs altogether after the conclusion of the war.

James Pierpont made very little money from “Jingle Bells,” and keeping his credit on the song was a struggle. The song remains one of the best-known worldwide. Impoverished and forgotten, Pierpont died at seventy and, according to his wishes, was interred next to his brother at Laurel Grove Cemetery, Savannah.

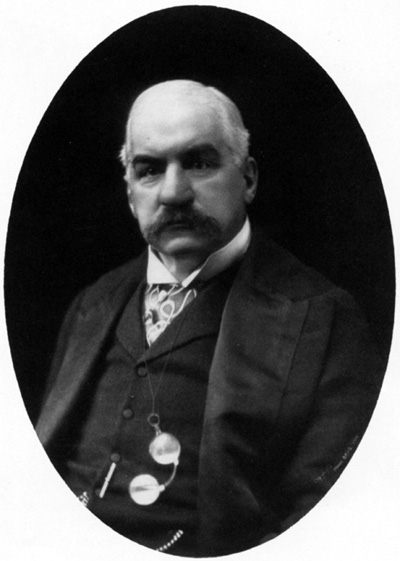

On an ironic note, the destitute songwriter was the uncle to a man of considerable wealth: the great American financier J. Pierpont Morgan.